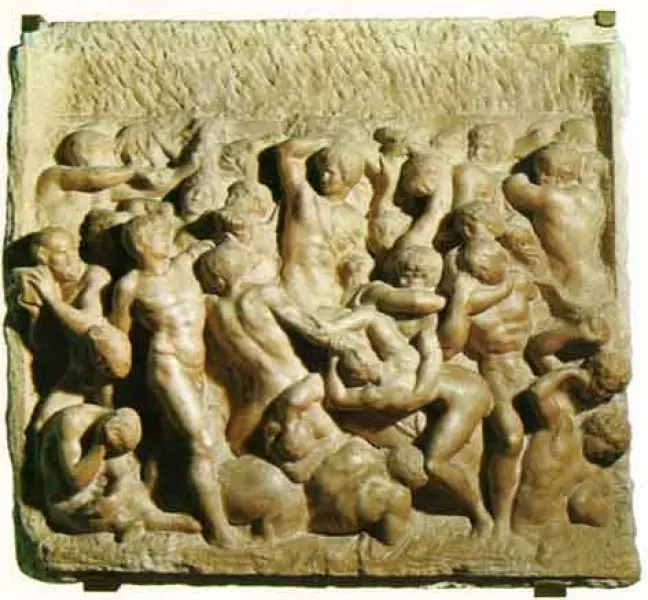

Centauromachia

L'opera, un rilievo su lastra di marmo, delle dimensioni di 84,5X90 cm., appartiene al periodo giovanile di Michelangelo, si trova nella Casa Buonarroti a Firenze. Risale al 1492, è stata realizzata quando il Buonarroti aveva 17 anni.

Il soggetto che sembra gli sia stato suggerito da Poliziano. Il riferimento all'antico mito greco - quello della battaglia tra i Centauri e i Làpiti - tratto dalle Metamorfosi di Ovidio, fu tuttavia solo un pretesto.

E' classica anche per l'ispirazione agli antichi sarcofagi romani, ma è una composizione molto libera in cui abbandona le formule tradizionali.

Questo rilievo non è solo una prova di bravura del giovane artista esordiente, è anche il punto d'arrivo delle ricerche quattrocentesche sul nudo e l'avvio di una nuova concezione plastico-dinamica del corpo nello spazio.

Michelangelo non ha narrato la vicenda, non ha ricostruito la scena mitologica, ma ha voluto rappresentare una lotta furiosa tra guerrieri nudi dalla muscolatura tesa e possente.

La figura al centro, in maggiore evidenza, è il perno di tutta l'azione. Dal suo gesto, con il braccio destro alzato e la torsione del busto, si genera un moto rotatorio che sembra trascinare tutte le altre figure. È lo stesso movimento che ritornerà cinquant'anni più tardi, nel Cristo Giudice del Giudizio Universale nella Cappella Sistina a Roma.

Protagonista assoluto è un corpo umano che esprime energia e movimento, con scorci, torsioni, intrecci, grovigli, in una lotta senza fine. Quasi una metafora della vita.

Lo spazio non è descritto: i pochi brani del fondo emergono grazie ai vuoti che separano un corpo dall'altro. Ma la profondità del fondo è molto ridotta, e in alcuni particolari, addirittura annullata, raggiunge quasi lo stesso livello delle figure.

Colpisce nell'opera il modo in cui lottano le figure: esse non si pongono solo l'una contro l'altra, ma è dalla materia che le imprigiona che sembra vogliano liberarsi con toni fortemente drammatici. La traccia ancora visibile dello scalpello, in particolare nella larga fascia in alto e nelle parti più in profondità, rende ancor più evidente la lotta delle figure che sembrano emergere a fatica dal marmo. Questa fatica di emergere, il prender vita dalla massa inerte del marmo, diventa anche l'immagine stessa della creatività dell'artista.

Lo spazio non è vuoto ma materico, concreto, e non è separato dalle figure che sono invece invischiate in quella materia e ne emergono solo grazie alla forza e alla loro energia interiore.

A. Cocchi

The Battle of Centaurs by Michelangelo

Michelangelo. The Battle of Centaurs. 1492. Marble relief. Florence, Casa Buonarroti

The Battle of Centaurs is a marble relief sculpture by Michelangelo from 1492 when he was only seventeen. Today it is housed at Casa Buonarroti, in Florence, Italy.

The subject seems to have been proposed by the poet Angelo Poliziano. The reference to the old Greek myth - the battle between the Centaurs and the Lapiths - taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses was just a pretext.

It's a classic composition inspired by the old Roman sarcophagi, but it’s a very free one in which the artist abandoned the traditional formulas.

This relief is not only a skill's test by the young apprentice, but it's also the culmination of the 15th century research about the nude and the start of a new concept of the body's plastic dynamism in the space.

Michelangelo didn't tell the story, neither did he reconstruct the mythological scene, but he wanted to represent a fierce battle between naked warriors of tense and powerful musculature.

The highlighted centre character is the pivot of the whole action. From his position with a raised right arm and twisted torso, a rotary motion is generated, which seems to drag all the other characters. It's the same movement that returner 50 years later, with The Last Judgment with Christ as a judge in the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

The main protagonist is the human body expressing energy and movement, with twists, intertwinements and tangles in an endless battle. It's almost a metaphor of life. The space is not described: the little background that emerges is due to the empty spaces that separate one character from the other. But the background depth is reduced and in some points almost removed, nearly reaching the same level of the characters.

This work strikes in the way the characters fight: they not only stand one against the other, but it seems they want to be free from the matter that traps them using a very dramatic tone. The visible traces of the chisel, particularly in the wide top strip and in the deeper sections, render the fight even more obvious, with the characters that seem to emerge from the marble with difficulty. The struggle to emerge, the coming to life of the marble lifeless mass, become the very image of the artist's creativity.

The space is not empty but concrete and material. It's not separated from the characters that are mixed in that matter and that emerge only thanks to their power and interior energy.

A. Cocchi

Trad: A. Sturmer

Bibliografia:

E. Bernini, R. Rota Figura 1 Editori Laterza, Bari 2002

G. Cricco, F. Di teodoro Itinerario nell'arte. Vol 2, 2000

G.C. Argan, B. Contardi in: Michelangelo Dossier Art n. 9 Giunti, Firenze

C. Alchidini Luchinat, E. Capretti, K. Weil-Garris Brandt Michelangelo. Gli anni giovanili. Dossier Art n. 150 Giunti, Firenze